Networking

Reliable Data Transfer Protocols

Stop and Wait Protocols

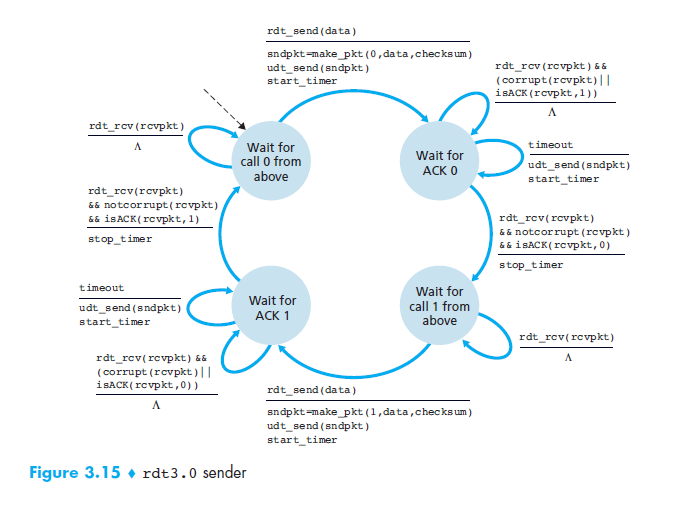

A simplified reliable data transfer protocol outlined in the book Computer

Networking: A Top-Down Approach by James Kurose and Keith Ross is a good

example of a stop and wait protocol. They refer to the protocol simply as

rdt3.0. Here is an image of the FSM for the sender routine.

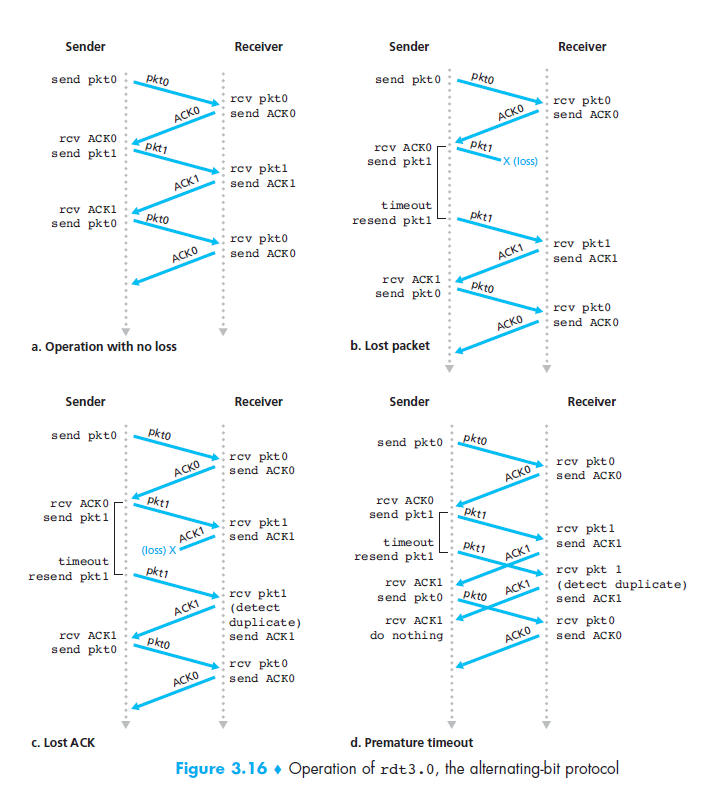

The protocol involves the use of checksums, sequence numbers, a timer, as well as the use of both positive and negative acknowledgments. If a checksum is calculated differently at the receiver than it was recorded as at the sender, then a negative acknowledgment is returned. If the checksum matches then a positive acknowledgment is returned. If the packet does not arrive at all then no acknowledgment will be returned and the timer at the sender will timeout and the lost packet will be retransmitted. If an acknowledgment is lost then the timeout will also occur causing retransmission. The following image from the Kurose Ross book shows the four main scenarios illustrated by the following timing diagrams

Only two different sequence numbers are used, 0 and 1, which are alternated between for each sucessful packet delivery. If you examine the above diagrams you will see why the sequence numbers are needed to keep up with which packet is which when a premature timeout expires but neither the packet nor the ACK has been lost. This introduces duplicate data packets in which case only the sequence numbers allow the protocol to handle correctly. Because of the alternating sequence numbers this type of protocol is also often referred to as an alternating-bit protocol.

This protocol is called a stop and wait protocol because it only tries to have one outstanding packet in the sender-receiver channel at any given time. In other words, it only sends the next packet after it is sure the current packet has been received correctly (through the indication of a postive acknowledgment).

Pipelined Protocols

The protocol rdt3.0 described in the Kurose Ross book is functionally

correct meaning that it can be shown that it will deliver packets correctly and

in order in ALL situations. However, the performance of rdt3.0 will be rather

poor due to the nature of stop and wait protocols. The fact that only one packet

is being sent at a time means that we will have utterly low link utilization.

Example of Performance of Stop and Wait Protocol

Consider two hosts situated rather geographically distant so that the

propogation delay between them will be relatively large. For a propogation delay

assumed to be at the speed of light, lets assume a propogation delay from one

end to the other will be P = 20 ms. Suppose they are connected on a high

speed gigabit channel with tansmission rate of

R = 1 Gbps = 10^9 bits per second, and sending packets of size

L = 2KB = 2,000 bytes. Since we have approximately 16,000 bits per

packet (headers and data), then the transmission delay can then be calculated

as

d_t = L / R = 16,000 b / 10^9 bps = 16 usec = 16 * 10^(-6) sec

If the sender begins transmission at t_0 = 0, then the last bit would enter

the channel at the sender side at t_1 = L / R = 16 usec. The packet would

travel at the speed of light, the first bit arriving at t_2 = P = 20 ms and

the last bit arriving at

t_3 = P + (L / R) = 20 ms + 16 usec = 20.016 ms

It will take the same amount of time for the receiver to send an acknowledgment to the sender. If we ignore the transmission delay for the very small ACK packet then it would arrive back at the sender at

t_4 = 2 * P + L / R = 40.016 ms

Only after this point in time, t_4 can the sender transmit another packet.

This means that the sender only has a link utilizatization of

U = (L / R) / (2 * P + L / R)

= (16 * 10^(-6)) sec / (40.016 * 10^(-3)) sec = 0.0004

In other words our stop and wait protocol was only able to acheive a link utilization of 0.04% in this case! This is not good. In order to solve this problem with stop and wait protocols, we use a technique known as pipelining. This technique is not only used in networking, but also heavily relied on in computer architecture as well and is employed by most modern processors.

Using pipelining in a reliable data transfer protocol will have some known consequences as well:

The number of sequence numbers used will have to be increased to accomodate the number of packets that can be oustanding in the sender-receiver channel at a given time.

The sender will have to buffer all the packets that have been transmitted but for which an acknowledgment has not yet been received. Buffering at the receiver may also be needed.

There are two approaches that are generally used in pipelining protocols to deal with error recovery.

Go-Back-N (GBN) Protocols

- Sender is able to transmit multiple packets if available and without waiting for acknowledgments.

- Sender cannot have anymore than some maximum allowable number,

N, of outstanding currently unacknowledged packets in the channel.

Kurose in ross are able to define four different intervals in the range of

sequence numbers used in a GBN protocol. If we define the sequence number of the

oldest unacknowledged packet as base, and the smallest unused sequence number

as nextseqnum, which is also the sequence number of the next packet to be

sent. Then the four intervals are defined as follows:

- The interval

[0, base - 1]covers sequence numbers that have been transmitted and acknowledged. - The interval

[base, nextseqnum -1]consists of sequence numbers of packets that have already been transmitted but are as of yet unacknowledged. - The interval

[nextseqnum, base + N-1]consists of packets which can be sent immediately if data arrives from the upper application layer. - The interval covering sequence numbers greater than or equal to

base+Ncannot be used until an unacknowledged packet, is acknowledged.

When an a given acknowledgment is received at the sender from the receiver, the Go-Back-N protocol may allow the sender to automatically acknowledge any unacknowledged packets with a sequence number less than the sequence number being acknowledged, even if no acknowledgment has actually been received for these packets. This is possible due to the fact that the sender knows that the GBN receiver will only ACK a packet if it has received all other packets with sequence numbers less than the received packet.

The range of sequence numbers that may be oustanding in the channel is usually thought of as a window of size N of packets that may be sent. The window slides as more packets are acknowledged. Because of this, the Go-Back-N and other protocols that operate similarly, are often also referred to as sliding-window protocols.

One might wonder why we limit the number of outstanding packets at all if this type of protocol will work. You may even reason that there is no need for such a limit. However, you'd be wrong. Flow control is one, but not the only, reason for this. Flow control is needed in order to ensure that the sender does not overwhelm the receiver. If we have a sender that is capable of sending at a much higher rate than the receiver is capable of receiving then we will have many dropped packets and utilization will suffer.

A packets sequence number is carried in a fixed-length field in the packet

header. Because we are using a fixed-length sequence number field we must have

a finite range of valid sequence numbers. If the number of bits used in the

sequence header is n then the range of valid sequence numbers will be

[0, 2^n - 1]. The sequence number space may, therefore, be though of

as a ring of size 2^n. The common reliable data transfer protocol in use

today, TCP, uses 32-bit sequence numbers. TCP sequence numbers also refer to

bytes in the stream rather than packets.

The following FSM diagrams from the Kurose Ross text illustrate the sender and receiver sides of the GBN protocol.

It's easy to think you understand how this protocol will work, but almost no one quite understands how it is going to work in every situation just by reading a description like I have provided. What I would recommend is checking out this open source java applet which simulates and visualizes a Go-Back-N protocol. You should go play with the Go-Back-N applet, first seeing how it works under normal conditions and then try killing some packets on the way to the receiver. Also try killing some acknowledgments on the way to the sender to see how it will work in all situations.

The name Go-Back-N is derived from the fact that when a timeout occurs on an unacknowledged packet, then the sender retransmits all of the currently unacknolwedged packets. The protocol only maintains a single timer for the oldest unacknowledged packet. If there are still additional outstanding unacknowledged packets in the channel when the acknowledgment for the oldest packet arrives, the timer is simply restarted for the next oldest packet.

Selective Repeat (SR) Protocols

The GBN protocol allows the pipeline between the receiver-sender to be relatively fully utilized. Hwoever, there are sscenarios in which the protocol's perfromance will suffer. If the window size and what's called the bandwidth-delay product product are both large then there will be many oustanding unacknowledged packets at any given time. In this situation a single packet error can cause the GBN protocol to retransmit many packets. If this happens often, then the many unnecessary retransmissions will fill the pipeline often and performance will suffer because of it.

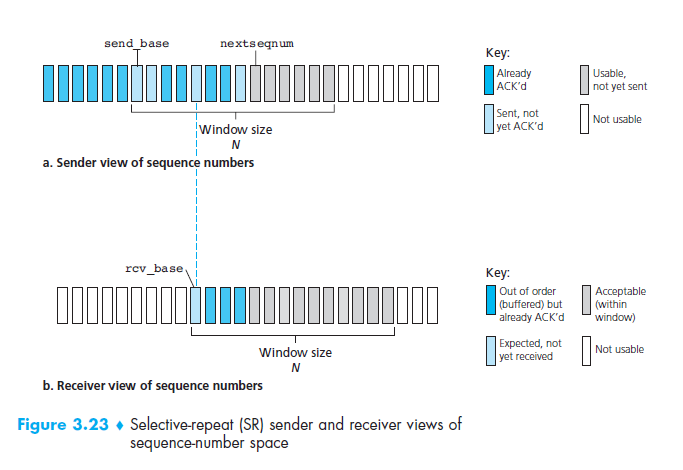

Selective repeat protocols attempt to avoid unneccessary retransmissions by

only retransmitting those packets that appear to have been lost or corrupted.

This is acheived by having the receiver individually, rather than

cumulatively, acknowledge correctly received packets. Again a window size of

N will be used to limit the number of currently oustanding packets in the

channel. However, unlike the GBN protocol, the SR sender will already have

received acknowledgements for some of the packets in the window and will keep

a timer for each unacknowledged packet. The following diagram illustrates the

view of the sequence number space and the window from the point of view of both

the sender and receiver.

The SR protocol receiver acknowledges correctly received packets regardless of whether they are out of order. Because of this the receiver must buffer out of order packets until any missing packets (with lower sequence numbers) arrive. At the point when the missing packets arrive, a batch of packets can then be delivered to the upper application layer.

Note that, unlike the GBN receiver, the SR receiver cannot ignore incoming retransmitted packets which have already been received (due to a lost or corrupted acknowledgment). This is necessary because if an acknowledgment is lost, the sender will eventually have to retransmit that packet before the window will advance beyond it. If the receiver ignores this retransmission then the sender's window would never advance any further. As a consequence, the sender and receiver will not always have an identical view of what has been received correctly. This also means that the sliding window for the sender and receiver will can be at different positions.

There are three events that an SR sender must act upon listed as follows:

- Data received from application layer.

- The sender determines the next available sequence number for the new packet to be created. If the sequence number is within the sliding window, then the packet is created and transmitted. If the next sequence number is beyond the sliding window's current position, then the sender will have to buffer the data or return it to the upper layer.

- Timeout waiting for an acknowledgment.

- A timeout must be kept for each unacknowledged packet in the channel. Upon a timeout expiring, the packet for which the timeout occured is retransmitted.

- Acknowledgment for a packet is received.

- Sender marks the packet as correctly received if it is in the window. If

and only if the acknowledgment sequence number is equal to

send_base(the first sequence number in the window), then the window is moved forward to begin at the next sequence number that has of yet has not been acknowledged.

- Sender marks the packet as correctly received if it is in the window. If

and only if the acknowledgment sequence number is equal to

There are also several events for which an SR receive must act upon:

- Sequence number

rcv_basecorrectly received.rcv_baseis packet with the samllest sequence number that has of yet to be received. The receivers window slides forward to begin at the next as of yet received packet, and all packets before this are delivered to the upper application layer.

- Sequence number within

[rcv_base + 1, rcv_base + N-1]correctly received.- The packet falls within the receiver's sliding window, however, there is

still at least 1 other packet,

rcv_base, which has not been correctly received. This packet must be buffered before it can be delivered to the application layer. It will only be delivered once all other outstanding packets with sequence numbers less than it have been received.

- The packet falls within the receiver's sliding window, however, there is

still at least 1 other packet,

- Sequence number within

[rcv_base - N, rcv_base - 1]correctly received.- This is a packet that the receiver has already previously acknowledged. This happens due to either a premature timeout, or a lost acknowledgment. In this case, another acknowledgment must be generated in order to ensure that the sender's window advances.

There is an applet, similar to the Go-Back-N Applet, which demonstrates the selective repeat protocol. You are encouraged to check out the Selective Repeat Applet and compare the two protocols.

Getting Rid Of Another Assumption

An assumption that we made in describing all three of the previous protocols is

that the underlying unreliable channel will not reorder packets. When reordering

can occur at the lower layers, then the effect is that a sequence numbers may

arrive that are in neither the sender nor the receivers current window. The

solution to this problem is to ensure that sequence numbers are not reused until

the sender is certain that the a packet with the given sequence number could not

possibly be somewhere in the network. This is implemented in practice by having

a maximum packet lifetime that a packet can live in the network. This is known

through the use of the TTL field in the IP datagram header utilized in the

network below the reliable data tranfer protocol. TCP assumes a maximum packet

lifetime of approximately 3 minutes as defined in RFC 1323.

Connection-Oriented Protocols

TCP, the Web's transport-layer, does in fact rely on many of the principles and approaches outlined above in the previous classifications of protocols. These include error detection, retransmitted lost/corrupted packets, cumulative acknowledgments, packet timers, and sequence numbers. However, TCP also employs a technique known as connection-oriented transport. This means that in order for two processes to communicate using the protocol, they must first establish a connection. This is accomplished through what is known as a handshake consisting of sending setup packets sent in order to estbalish the data transfer on both the sending and receiving ends.

A transport-layer protocol that sets up a connection in a manner similar to TCP does not have a connection in the physical sense between sender and receiver such as is the case in circuit-switched networks. The intermediate network components (routers) do not maintain the connection state, and it is setup, torn down, and maintained completely at the end systems. Routers are completely oblivious to upper-layer protocols.

A TCP connection can provide a full-duplex channel meaning that data can be sent in both directions between two processes simultaneously. A TCP connection is also always point-to-point meaning that there are only two end points between which the connection exists. A technique known as multicasting, in which data is transferred from one process to many simultaneously, is not possible with TCP due to the point-to-point nature of its connections.